The latching end effector, or LEE, functions as the equivalent of a hand on the Canadarm 2, allowing it to grasp incoming cargo ships and perform an increasingly ambitious set of maintenance tasks.

In the 1990s, Toronto Blue Jays centre fielder Devon White was famous for his ability to make graceful, leaping catches that seemed to defy the laws of physics.

Just up the road, engineers at Spar Aerospace in Brampton, Ont., were designing the Canadarm 2, little realizing that their creation would eventually be called upon to perform feats as improbable as Mr. White’s golden glove moves – but with 10 tonne space capsules instead of fly balls.

“We didn’t come close in terms of envisioning the amount that the arm would get used over the years … or all the things that we ended up using it for,” said Layi Oshinowo, who joined the team in 1995 and is now director of robotics and automation for Spar’s corporate successor, MDA Robotics, part of Maxar Technologies.

On Monday, the overachieving arm will achieve a career milestone when, for the 30th time, it reaches out from its perch on the International Space Station and snags an unmanned vehicle, in this case a Space X Dragon laden with equipment and supplies. Fittingly, the capsule is carrying a latching end effector, a copy of one of the cylindrical “hands” at both ends of the Canadarm 2, which is needed as a backup because the arm has been seeing so much use.

The capture of an incoming spacecraft is one of those manoeuvres for which the arm was not originally designed and it has become a huge cost saver. It means that a visiting capsule does not have to come equipped with a sophisticated navigation system for docking with the station. It just has to get close enough for the arm to reel it in safely.

“It’s critical the way you line things up,” said Mr. Oshinowo, adding that engineers have tweaked their software over the years to minimize loads on the 17.6 metre arm as it manipulates a free-flying vessel with many times its own mass.

Since the NASA space shuttles stopped flying in 2011, the arm has played an indispensable role in the the movement of gear to and from the station. The capture move is one of the few in which the arm remains under the control of someone on board the station. For a multitude of other maintenance tasks it is now far more common for the arm to be guided by an operator at mission control in Houston or in Saint-Hubert, Que., where the Canadian Space Agency has its headquarters. This evolution has taken the load off of busy astronauts while reducing the need for hazardous space walks, to the point where the arm functions like an additional crewmember on call.

The system comes in three parts (the entirety of which is illustrated on the back of the Canadian five dollar bill). In addition to the arm, which can detach at either end, there is a mobile servicing platform that rolls up and down the station’s main truss. And there is Dextre, the multilimbed robot that can sit at the end of the arm to perform human-scale tasks such as swapping out batteries or unloading a cargo ship.

The full set up requires four end effectors plus one spare. But all that capturing of cargo ships has meant that the end effectors on the arm have seen significant wear and tear. One of them finally experienced a failure last fall, prompting a series of swaps aboard the station.

“We were able to do a kind of shell game,” said Ken Podwalski, director of space operations and infrastructure for the Canadian Space Agency, describing how the hands were shuffled around to forestall another failure.

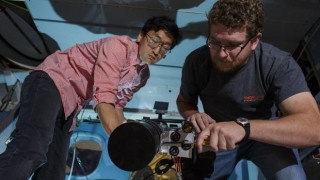

That comes to an end with this week’s delivery. The newly arriving end effector was formerly an engineering model, which Mr. Oshinowo and his team have spent years making flight ready at the space agency’s request.

Meanwhile, the end effector that is being replaced will soon be on its way back to Brampton for inspection and refurbishment after 17 years in orbit, making it a unique science project.

“It will be a kind of homecoming,” Mr. Oshinowo said, describing how the end effector will be useful for testing predictions about how different materials and systems on the Canadarm hold up in the space environment.

The extent to which Canada benefits from that data depends on federal Industry Minister Navdeep Bains, who has promised to release a long-awaited space strategy in the coming months.

As a key pillar of that strategy, proponents of Canada’s space sector would like to see Ottawa sign on to provide robotics for the next international space project, currently envisioned as a more compact but distant human outpost in orbit around the moon.

Through its constant use, Canadarm 2 has effectively earned Canada’s place in such an undertaking, Mr. Podwalski said.

“We are absolutely capable of doing these things. We’re capable of it now.”

IVAN SEMENIUK

SCIENCE REPORTER

The Globe and Mail, July 2, 2018