Transport Minister Marc Garneau says Canada is evaluating intelligence passed on by the United States to determine if it should require passengers travelling from some Middle East countries to pack all large electronic devices other than mobile cellphones in their checked baggage.

U.S. Homeland Secretary John Kelly spoke by telephone Tuesday with Mr. Garneau to explain why the Trump administration has ruled that only cellphones and smartphones will be allowed in the passenger cabin of flights into the United States from 10 airports in eight Muslim-majority countries.

“He made us aware of a situation that we are analyzing very carefully. We will have a fulsome discussion within government and look at the information that has been presented to us and then we will make a decision,” Mr. Garneau told reporters.

The U.S. directive, compounded with a subsequent ban of large electronics for some travellers headed to Britain, has caught global airlines and travellers in a wave of uncertainty as Canada now also mulls a similar ban and transport officials remain tight-lipped as to their reasoning.

Mr. Garneau would not say what type of security threat the Americans are concerned about, but it was reported by The New York Times that intelligence showed Islamic State is developing a bomb hidden in portable electronics. Mr. Garneau would not give a specific timeline for action to be taken but said the government will “act expeditiously.”

“As a country that takes the security side of transportation very seriously, it is our duty and obligation basically to look at in detail the information that has been provided to us by other intelligence communities and we will do that and make the appropriate decisions,” he said.

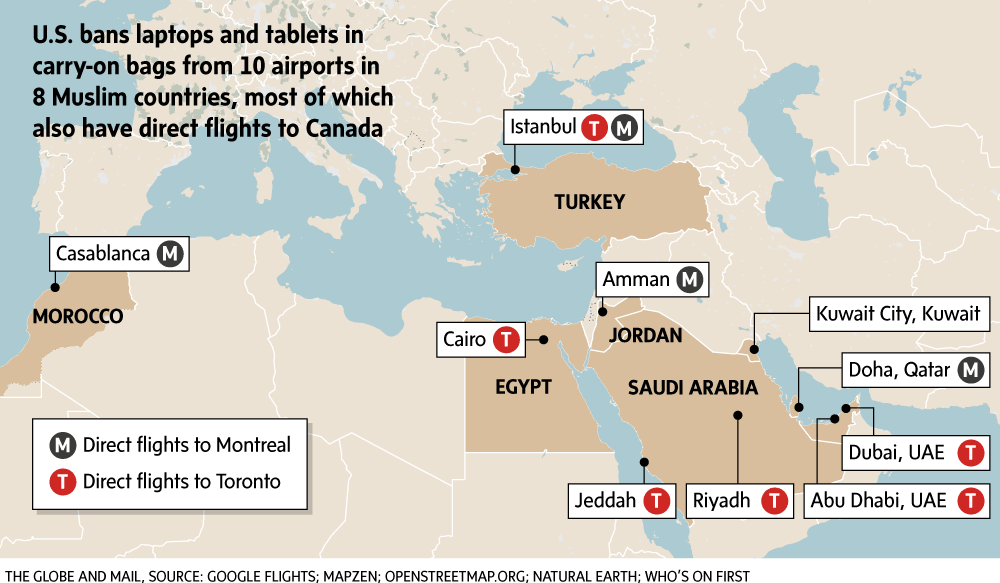

The U.S. ban affects flights from international airports in Jordan, Kuwait, Egypt, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Qatar and United Arab Emirates. About 50 flights a day will be impacted, all on foreign carriers.

An official said the Transport Department is seeking input from the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, the RCMP and Canada’s intelligence allies to assess the U.S. intelligence provided to the government. The official would not describe the nature of the threat passed on by the Americans.

Britain announced Tuesday that it is following the U.S. action with a ban applying to domestic and foreign flights coming from Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, Egypt, Tunisia and Saudi Arabia.

Of the nine airlines affected by the U.S. ban, eight offer direct routes to Canada, through either Toronto’s Pearson International Airport or Montreal’s Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport.

If Canada were to follow a similar ban, among the routes affected could be Turkish Airlines flights from Istanbul to Montreal, Royal Jordanian Airlines flights between Amman and Montreal and Qatar Airways flights between Doha and Montreal.

Representatives from two affected carriers, Etihad Airways and Royal Jordanian Airlines, said Tuesday the directives they had received so far had only applied to U.S.-bound flights.

Since Canada has not yet imposed a ban, Air Canada is not affected. The carrier flies three times a week to Dubai, but stopped flying to Istanbul last year.

“If the threat is real, I think the Canadian air security and intelligence apparatus would have to take a pretty hard look at it,” said airline industry consultant Robert Kokonis, who heads AirTrav Inc.

“If we don’t see Canada reciprocating, either there was no real hard intelligence … or if there was hard intelligence, it was only U.S.-destined flights.”

Robert Mann, a New York-based aviation expert, wondered why Abu Dhabi is included in the U.S. ban.

“Abu Dhabi has a state-of-the-art U.S. customs and immigration preclearance facility that was purposely built about two years ago to serve as a remote preclearance centre much as U.S. travellers preclear in Canada for flights to the U.S.” he said.

If the issue is that the screening process at the Middle Eastern and African airports is insufficient including Abu Dhabi, “it becomes a head-scratcher,” he said. “Why did we do that?”

The ban begins just before Wednesday’s meeting in Washington of the U.S.-led coalition against the Islamic State. A number of top Arab officials were expected to attend the State Department meeting. Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland is one of the participants.

U.S. officials said the decision had nothing to do with President Donald Trump’s efforts to impose a travel ban on six majority-Muslim nations. Homeland Security spokeswoman Gillian Christensen said the government “did not target specific nations. We relied upon evaluated intelligence to determine which airports were affected.”

On March 6, President Trump signed a revised executive order barring citizens from Iran, Libya, Syria, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen from travelling to the United States for 90 days. Two federal judges have halted parts of the ban, saying it discriminates against Muslims. Mr. Trump has vowed to appeal up to the Supreme Court if necessary.

The carriers from the effected countries have until Friday to comply with the new policy, which took effect early on Tuesday and will be in place indefinitely.

Several of the carriers, including Turkish Airlines, Etihad and Qatar, said early on Tuesday that they were quickly moving to comply. Royal Jordanian and Saudi Airlines said on Monday that they were immediately putting the directive into place.

An Emirates spokeswoman said the new security directive would last until Oct. 14. However, Ms. Christensen termed that date “a placeholder for review” of the rule.

The policy does not affect any American carriers because none fly directly to the United States from the airports, officials said.

Officials did not explain why the restrictions only apply to travellers arriving in the United States and not for those same flights when they leave from there.

The rules do apply to U.S. citizens travelling on those flights, but not to crew members on those foreign carriers. Homeland Security will allow passengers to use larger approved medical devices.

Angela Gittens, director-general of airport association ACI World, likened the move to the years-long restrictions of liquids on planes, which she said also came suddenly, in response to a perceived threat, and caused some disruption.

Airlines will adjust to the electronics policy, she said. “The first few days of something like this are quite problematic, but just as with the liquids ban, it will start to sort itself out.”

Reuters reported Monday that the move had been under consideration since the U.S. government learned of a threat several weeks ago.

U.S. officials have told Reuters the information gleaned from a U.S. commando raid in January in Yemen that targeted al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) included bomb-making techniques.

AQAP, based in Yemen, has plotted to down U.S. airliners and claimed responsibility for the 2015 attack on the office of Charlie Hebdo magazine in Paris.

The group claimed responsibility for a Dec. 25, 2009, failed attempt by a Nigerian Islamist to down an airliner over Detroit. The device, hidden in the underwear of the man, Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, failed to detonate.

ROBERT FIFE, JOSH O’KANE AND GREG KEENAN

The Globe and Mail

Published Tuesday, Mar. 21, 2017 7:05AM EDT

Last updated Wednesday, Mar. 22, 2017 7:34AM EDT